Tutorial for targeted property-based testing

By Andreas Löscher and Kostis SagonasSometimes random generation of input is not sufficient to find bugs in a reasonable amount of time. PropEr provides an extension to random property-based testing (PBT) called targeted PBT that guides the input generation towards values that have a higher probability of falsifying a property. To do this, users have to however specify a few additional ingredients for their properties e.g. appropriate search goals.

In this tutorial, we will show the limitations of random input generation on an example and then show how PropEr can use targeted PBT to overcome these limitations.

Labyrinth

Let us assume that we are implementing a game where the player has to reach the exit of a labyrinth. To make the game fair and fun we want to make sure that the exit is reachable from the entrance of the labyrinth. The labyrinth itself is an area enclosed in walls, and this area can contain additional wall obstacles. The player can move in four directions: up, left, down, and right.

In the Erlang program, the labyrinths (mazes) are given as a list of strings:

maze(0) ->

["#########",

"#X E#",

"#########"].The # represents a wall, the X the exit, and the E the entrance of the

maze. In this simple maze, the player can reach the exit by going left six

times. To access the maze data more easily, we convert the list of strings into

a map with the function draw_map(). For each position of the maze that

contains something interesting we store in the map the type, e.g. wall or

exit. We additionally store the locations for the exit and the entrance.

1> labyrinth:draw_map(labyrinth:maze(0)).

#{entrance => {1,7},

exit => {1,1},

{0,0} => wall,

{0,1} => wall,

...

{1,1} => exit,

{1,7} => entrance,

...}To test that the player can reach the exit from the entrance we generate a path and then calculate where the player ends up at. Our generator looks as follows:

step() ->

oneof([left, right, up, down]).

path() ->

list(step()).To calculate the final position we implement the function follow_path(). If

the player at some point reaches the exit when following the path she will not

proceed further and the exploration is finished successfully. The rest of the

path is ignored. If a step would lead into a wall this step is also ignored.

We can now implement our property to test:

prop_exit_random(Maze) ->

MazeMap = draw_map(Maze),

#{entrance := Entrance} = MazeMap,

?FORALL(Path, path(),

case follow_path(Entrance, Path, MazeMap) of

{exited, _} -> false;

_ -> true

end).The property is parameterized with the maze so that we can easily test

many different mazes. Since we are only interested in if the exit is reached

and not the final position of the player, we ignore the returned position from

follow_path(). Note that we expect this property to fail if the mazes contain

a path from the entrance to their exit:

18> proper:quickcheck(labyrinth:prop_exit_random(labyrinth:maze(0))).

.......................................................!

Failed: After 56 test(s).

[up,left,left,down,up,left,down,left,down,left,down,up,left,up,down,down,right,left,right]

Shrinking ..........(10 time(s))

[left,left,left,left,left,left]

falsePropEr finds a path to the exit in just a few tests and shrinks it down to six steps to the left. The property seems to work as expected. We can now test a more complicated maze:

maze(1) ->

["######################################################################",

"# #",

"# E #",

"# ##### #",

"# ##### #",

"# ##### ##### ##### #",

"# ##### ##### #",

"# ##### ##### #",

"# ##### #",

"# ##### #",

"# ##### #",

"# ##### ########## #",

"# ##### ########## #",

"# ##### ##### ########## #",

"# ##### #",

"# ##### #",

"# ##### #",

"# ##### #",

"# ##### ##### #",

"# ##### #",

"# ##### #",

"# X #",

"# #",

"######################################################################"].Since this labyrinth is both bigger and more involved, we increase the amount of tests to lets say one million:

23> proper:quickcheck(labyrinth:prop_exit_random(labyrinth:maze(1)), 1000000).

.................... <1.000.000 dots> ....................

OK: Passed 1000000 test(s).

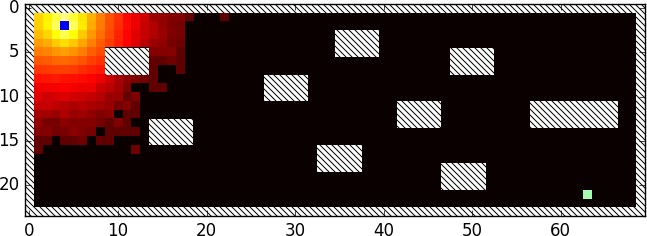

trueThe property passes, but we can clearly see that there is a path leading from the entrance to the exit. To further analyze what is going on we record the final positions of the player and build a heatmap:

The heatmap shows, that the final positions of the player are concentrated around the entrance. (In fact,the final positions are following a normal distribution around the entrance.)

Each step in the list is generated randomly and independently from the other steps. This means that for long paths the steps in it mostly cancel each other out (one step left and one step right is equivalent with taking no steps at all). Another issue is that the input for each test is generated independently from all other tests. That means that already explored areas are covered again; even if they lead away from the exit are explored again. Ideally, we want to learn from the paths that we already explored and use them to construct ones that lead the player to the exit.

Targeted Property-Based Testing

PropEr provides an enhanced form of random property-based testing (PBT) called targeted property-based testing where the input generation is not completely random anymore but guided by a search strategy. Instead of generating inputs which are independent from each other, the search strategy uses information gathered by previous tests in form of utility values, to generate the next input. The user can then instruct the search strategy to either maximize or minimize these utility values.

The general structure of a property that can be tested with targeted PBT looks as follows:

prop_Target() -> % Try to check a property

?FORALL_TARGETED(Input, Generator, % by using a search strategy

begin % for the input generation.

UV = SUT:run(Input), % Do so by running SUT with Input

?MAXIMIZE(UV), % and maximize its Utility Value

UV < Threshold % up to some Threshold.

end)).We can specify the search strategy PropEr will employ in the options given to proper:quickcheck(Prop, Options). For example, to use simulated annealing, the default search strategy of PropEr we test a property with the following call:

proper:quickcheck(prop_Target(), [{search_strategy, simulated_annealing}, {search_steps, 1000}]).The search_steps option specifies how many search steps PropEr uses. This option is independent from the numtests option that PropEr uses for random testing. The default values for search_strategy is simulated_annealing and the default value for search_steps is 1000, like in the example above (we could for example omit the search_strategy option if we use simulated annealing).

PropEr constructs all definitions that the search strategy requires automatically. In the case of simulated annealing, this means that a neighborhood function is constructed, a function that produces a random instance of the input that is similar (in the neighborhood) to a given input instance.

Furthermore, we need to tell the search strategy where the search should be

going. This is done by reporting to the search strategy the utility value of

the currently tested input and weather to maximize or minimize these values

with ?MAXIMIZE or ?MINIMIZE. The utility values capture how close input

comes to falsifying property.

NOTE: PropEr can produce a neighborhood function automatically from a generator. In this tutorial, we will first write such a function by hand and then compare it to the automatically generated one. To effectively use targeted PBT it is important to understand how neighborhood functions can be written.

Targeted Testing

We can use this technique to test our labyrinths and improve the chance of finding a path to the exit significantly. We know the location of the exit that we want to reach and the final position of the player when following a path. We can calculate the distance between this final position and the exit:

distance({X1, Y1}, {X2, Y2}) ->

math:sqrt(math:pow(X1 - X2, 2) + math:pow(Y1 - Y2, 2)).Now we can write prop_exit_targeted_user():

- We exchange

?FORALLwithFORALL_TARGETEDto use simulated annealing as search strategy. - We calculate the distance

Dbetween the final player position and the exit and tell PropEr to minimize this distance with?MINIMIZE(D) - Finally we tag the

path()generator with theUSERNF()macro and add the neighborhood functionpath_next():

prop_exit_targeted_user(Maze) ->

MazeMap = draw_map(Maze),

#{entrance := Entrance, exit := Exit} = MazeMap,

?FORALL_TARGETED(Path, ?USERNF(path(), path_next()),

case follow_path(Entrance, Path, MazeMap) of

{exited, _Pos} -> false;

Pos ->

UV = distance(Pos, Exit),

?MINIMIZE(UV),

true

end).

The neighborhood function path_next() should produce a random input that is

in the neighborhood of the base input, that is a similar input to the base

input. For our path we can just add an extra step:

path_next() ->

fun (PrevPath, _) ->

?LET(NextStep, step(), PrevPath ++ [NextStep])

end.If we test this property, now it typically fails after just a few hundred tests:

33> proper:quickcheck(labyrinth:prop_exit_targeted_user(labyrinth:maze(1)), 10000).

.................. <572 dots> .....................!

Failed: After 572 test(s).

[up,right,right,down,right,up,up,right,down,left,down,down, ..., down]

Shrinking ................................................................................................(96 time(s))

[right,right,right,right,right, ..., down]

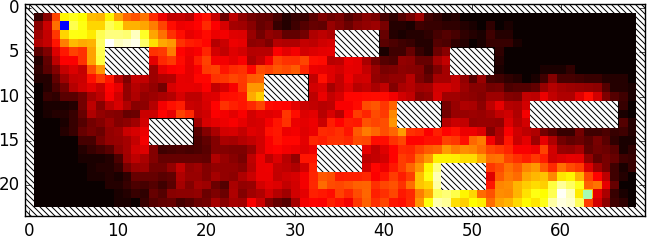

falseIf we produce a heatmap similar to the one for random input generation we can see that the generated paths go towards the exit of the maze:

Targeting Performance

Right now we are only adding one step at a time for each search step. We can decrease the amount of tests needed by adding let’s say 20 steps at a time. If we construct a bad path it will be rejected in the same way but if we construct a good path we will skip multiple intermediate steps:

path_next() ->

fun (PrevPath, _) ->

?LET(NextSteps, vector(20, step()), PrevPath ++ NextSteps)

end.Now the property usually fails less than a few 100 search steps:

36> proper:quickcheck(labyrinth:prop_exit_targeted_user(labyrinth:maze(1)), [10000, {search_steps, 5000}]).

.................. <285 dots> ........................................!

Failed: After 285 test(s).

[left,up,right, ...]

Shrinking .......... ... ..........(100 time(s))

[right,right,right, ..., right]

falseResetting Bad Runs

With our targeted property in place, we can now try out an even more complicated maze:

maze(2) ->

["######################################################################",

"# #",

"# X #",

"# #",

"# # ######## ##### #### ######## #",

"# ### ## ## # ## # ## #",

"################ ## ##### #### ## #",

"# ### ## ## ## # ## #",

"# # ## ## #### ## #",

"# #",

"# #",

"# # #",

"# # #",

"# # #################################",

"# # #",

"# # #",

"# # #",

"# #################################### #",

"# #",

"# #",

"################################ #",

"# E #",

"# #",

"######################################################################"].When we test prop_exit_targeted_user() with maze 2 we see that sometimes

the property fails very fast. In other cases however, the property takes many

tests to fail. We can also see that the tests become really slow after a while.

The reason is that we add more and more steps and the path becomes longer with

each test. There are several solutions to this:

- We could write a more complicated neighborhood function that also removes some steps, or one that takes previously visited positions into account when deciding which steps should be taken next. However, we can see that in some cases our existing neighborhood function is sufficient to find the input fast.

- We can reset the search after the path reaches a certain length and start constructing a new path form the entrance.

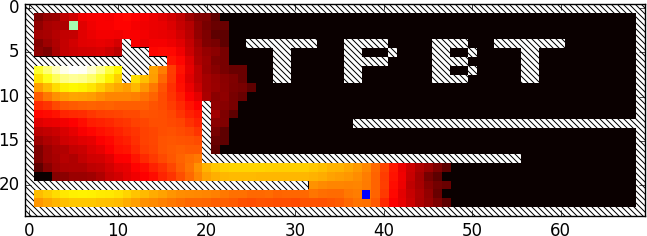

To help us with our decision we record the final positions for each generated path for a low amount of tests and accumulate the data over multiple runs. We then build a heatmap from this data:

We can see multiple bright spots on the left side and under the arrow. This probably means that the search gets stuck and has a hard time escaping from these areas. We can also see that there are quite a few runs that find the exit. Resetting the search should be sufficient to solve our problem:

prop_exit_targeted_user(Maze) ->

MazeMap = draw_map(Maze),

#{entrance := Entrance, exit := Exit} = MazeMap,

?FORALL_TARGETED(Path, ?USERNF(path(), path_next()),

case follow_path(Entrance, Path, MazeMap) of

{exited, _Pos} -> false;

Pos ->

case length(Path) > 2000 of

true ->

proper_sa:reset(),

true;

_ ->

UV = distance(Pos, Exit),

?MINIMIZE(UV),

true

end

end).The function proper_sa:reset() discards the current state of the search and

starts from the beginning initial input. If we test the property now it will

fail after a few thousand tests:

36> proper:quickcheck(labyrinth:prop_exit_targeted_user(labyrinth:maze(2)), [10000, {search_steps, 5000}]).

.................. <2339 dots> ........................!

Failed: After 2339 test(s).

[down,left,up, ..., down]

Shrinking ...................................................................(67 time(s))

[left,left,up, ..., left]

falseNOTE: Resetting bad runs can be an effective method to improve the testing performance. One must be however careful when choosing the cutoff value. If we choose a value of let’s say 500 instead of 2000 then the property will fail fast for maze(2) but it will fail less reliably for maze(1). The reason is, that the distance between entrance and exit in maze 1 is larger and more steps are needed to reach the exit.

PropEr’s constructed Neighborhood Function

PropEr can construct neighborhood function automatically from the random generator. In order to use such a constructed NF we just need to remove the ?USERNF macro from the property:

prop_exit_targeted_auto(Maze) ->

MazeMap = draw_map(Maze),

#{entrance := Entrance, exit := Exit} = MazeMap,

?FORALL_TARGETED(Path, path(),

case follow_path(Entrance, Path, MazeMap) of

{exited, _Pos} -> false;

Pos ->

UV = distance(Pos, Exit),

?MINIMIZE(UV),

true

end).This property will fail consistently for all examples, even if we don’t reset bad runs. The neighborhood function that PropEr automatically generates usually works reasonably well for simple generators such as path/0. (In this particular case, it works very well.) When dealing with more complex generators, some manual work is required. The next tutorial will cover how we can adjust the automatically constructed neighborhood functions to avoid writing them by hand.

You can get the complete final code of this tutorial by clicking on the following link: labyrinth.erl.